I’ve been recently getting into Delicious in Dungeon and, unfortunately for my work schedule, the hype is real. Naturally, this got me thinking about how you make foraging and cooking work in games.

Cooking in games feels like one of those cursed problems where any solution you come up with will be great for your group and terrible for everyone else. I lump it in with crafting, alchemy, enchanting, etc. because nobody seems to agree on how these things should work. So we end up with hundreds of different solutions that all are either too complicated or feel way too shallow.

I’m happy to tell you everyone else is an idiot, and I’ve solved the problem. You’re welcome!

Delicious in Dungeon shows that the dungeon the characters inhabit is an ecosystem that they’re interrupting. Contrary to the “mythic underworld” concept (despite taking inspiration from it in the actual physical construction of the dungeon), the “dungeon as ecosystem” concept is a strong one that feels really good to discover as play goes on.

I’ve been chatting with friends about this show and how you could do something similar in ttRPGs. Cooking selection isn’t a new concept in these games (see: the hundreds of generators out there for creating tavern menus), nor is the idea of the dungeon being an ecosystem (Dragon Magazine, Issue 2111 and literally every other “The Ecology of…” article written in that magazine2).

But the problem with these solutions is that they feel reactive, rather than proactive. You’re not generating menus for every tavern in your world or developing a global dungeon ecosystem before you sit down for session one.

What happens is you create these things on the fly, and in the broader sense, they break down over time. Does every tavern have dragon whiskey? Does every dungeon have to have a bespoke reason for why oozes exist? What makes this creature edible and another one inedible?

Another issue is that everything is way too complicated in many third-party books on harvesting and crafting. You usually have to make a check to identify what ingredient you want, a check to harvest said ingredient, a check to determine a recipe for its use, a check for making the recipe, etc. It ends up feeling like the GM doesn’t want you to be engaging in the system, and with enough failures at some of these checks, the players aren’t going to want to either.

So what is the solution? I think whichever direction you go, you need to start with the bestiary/monster manual. This is where the GM will want to have the information players ask for once they hunt or slay the things they want to harvest.

But what actually goes in there? Is there such a thing as too much information? Let’s see what it looks like with three different levels of intensity.

1. The Chef Method

Description: Food is food and unless its spiritual, it really only works in sustaining your energy and staving off hunger.

This is probably the simplest solution to apply. Whether it’s a dryad or a dragon, their parts are functionally no different than a carrot or a cow.

In some cases, eating or cooking monster parts requires a bit of setup, such as needing to wait for a dragon’s internal furnace to cool down before handling or wearing some kind of breathing apparatus to prevent breathing in a dryad’s spores.

But, again, food is food.

A few requirements for this method to work:

Hunger and Thirst. Because eating the monsters has no mechanical benefit most of the time, characters must feel like killing, cooking, and eating monsters is beneficial in other ways. Such as, y’know, not starving to death.

Unavailability / Impracticality of Other Options. Rations and other mundane foodstuff would need to be incredibly modest, offering only the bare minimum of hunger and thirst necessities. Traditional food doesn’t grow in the dungeon, necessitating hunting and harvesting.

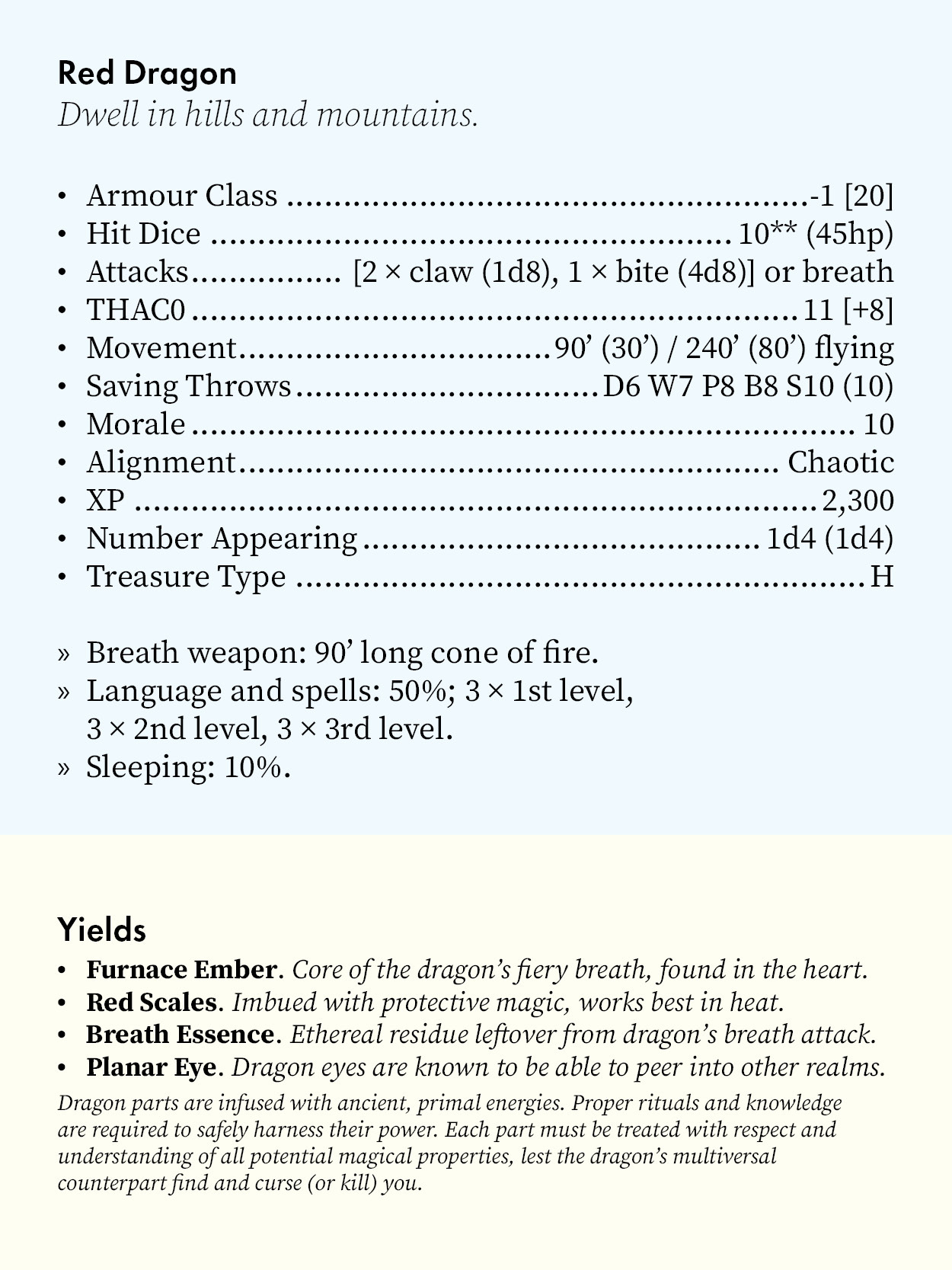

Here’s what the Old-School Essentials Red Dragon stat block might look like using the Chef Method:

2. The Witch Method

Description: Yields are about magical properties, which are explained in narrative terms over mechanical rules.

Again, this isn’t too much of a lift from what you'd naturally be able to come up with at the table. We move away from mundane food and into a narrative territory where the harvest yields more or less prompt the players to investigate and explore.

Here’s what the same stat block might look like using that approach:

For a player harvesting Breath Essence, how can they use that? Moreover, how do they extract it? You as the GM can ask these questions and they can come up with applications themselves. Or you can quickly use any of these as a plot hook to get the players traveling the land for answers.

3. The Apothecary Method

This is your bread-and-butter harvesting block that gives you percentage chance on yields (in this example, roll percentile and add whatever bonus due to tools, expertise, or whatever matters) and those yields have concrete effects:

Conclusion

Regardless of your method, the important thing is that these should be located in the place that’s easiest to reference and serves more than one purpose: the monster manual or bestiary for your game!

In a full-size bestiary, you might even include all three methods near the stat block, allowing you, the GM, to pull levers depending on how complicated or simple you want the harvesting to be.

Thanks to the following paid subscribers of the Grinning Rat Newsletter:

Azzlegog, Michael Phillips, Mori

Your support is what makes this newsletter a joy and privilege to write. Thank you, again!

If you’d like to support the newsletter, consider becoming a paid subscriber. You’ll get a shoutout at the end of each article (like the fine folks above) and you’ll help me pay for my morning coffee.

The Ecology of the Dungeon, by Buck Deason Holmes. Dragon Magazine, Issue 211.

Ecology is a long-running series of articles in Dragon and Dungeon magazines, focusing on detailed information on various monsters and creatures.

I think it was the Orcs of Thar Gazetteer from BD&D which had something about how much meat per HD a creature yields. It didn't go into it too deep, but did cover some basics of how many animals you needed to steal in a raid to feed your tribe.

I'm reading Wilderfeast at the moment and they're doing more of a 2 (maybe 3), but they do have a bestiary and ingredients in each area listing!