Skip the Gold; Give Better Treasure

Gold is simple, ubiquitous, mundane. Let's create treasure that is anything but.

The Italian painter Raphael might have stood at his easel in a candlelit Roman workshop in the early 16th century, carefully layering paint onto the canvas that would become his Portrait of a Young Man.

Completed at the height of his career, the piece would remain in his studio for several years — only to likely be bundled among other paintings, sketches, and self-portraits after his untimely death in 1520.

Hailed as one of the Italian Renaissance’s crowning achievements — and possibly a self-portrait of the painter himself — Portrait of a Young Man radiates a mastery of form and light. At the time, however, Raphael likely had no reason to predict how tumultuous of a life the painting would have after his own life had ended.

Nearly two hundred years later, in the 18th century when Adam George Czartoryski — a Polish nobleman determined to protect his nation’s cultural legacy — added the painting to the famed Czartoryski Collection founded by his mother Izabela Czartoryska (which you can still visit today! Europe is crazy like that!) alongside other masterpieces including some by Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael’s work became a symbol of Poland’s cultural resilience, particularly during an era when partitions and foreign domination beset the country.

World War II came one hundred and fifty years later, in the early-to-mid-20th century. With it, the Gestapo — under Governor-General Hans Frank — plundered the Czartoryski Museum and seized this Renaissance gem for Adolf Hitler’s planned Führermuseum.

Numerous secondary sources claim Frank praised it as “one of the most beautiful works ever created.”

But as WWII ended and Nazi power collapsed, like millions of other priceless works, the painting disappeared.

Some claimed it was last seen in Frank’s personal retreat in Bavaria; others speculated it was destroyed or spirited away to a private collection.

To this day, no one knows where it is or if it still exists. We can, however, state a few things as fact:

The painting changed hands countless times, captivating everyone from aristocratic collectors who showcased it in lavish salons to high-ranking wartime officials who claimed it as spoils of conflict.

It has exerted a global pull that persists to this day.

Numerous organizations span continents to recover and restore looted paintings like this one, hoping to return them to the museums and families from which they were torn.

And while all that is true, perhaps, somewhere in an attic in a quiet European village, a child could one day brush aside cobwebs to find the missing treasure, never suspecting the countless hours and fortunes invested in its rediscovery.

To apply this to role-playing games, who’s to say that when a player character unearths a large portrait of a dwarven noble in the depths of a dungeon, they’re not uncovering a priceless object that has exchanged hundreds of hands, itself witness to a centuries-worth of history and legacy?

In most fantasy elf games, like DND, treasure is synonymous with monetary wealth: gold coins, gemstones, or art objects. As a transactional tool, this works. But it rarely delivers emotional or narrative impact.

To make matters worse, gold becomes trivial once a party amasses enough wealth. At that point, what can’t they buy? What does having thousands of gold pieces really mean?

Unless you’re an economist, not much. Ultimately, the problem with gold is its lack of purpose and connection to the broader world. As a reward, it rarely addresses the core motivations of the players or characters. It doesn’t signal achievement, confer power, or create lasting connections to the world.

Simply reskinning gold as gems or statues doesn’t solve the problem either; it just decorates it.

So, how do we fix this?

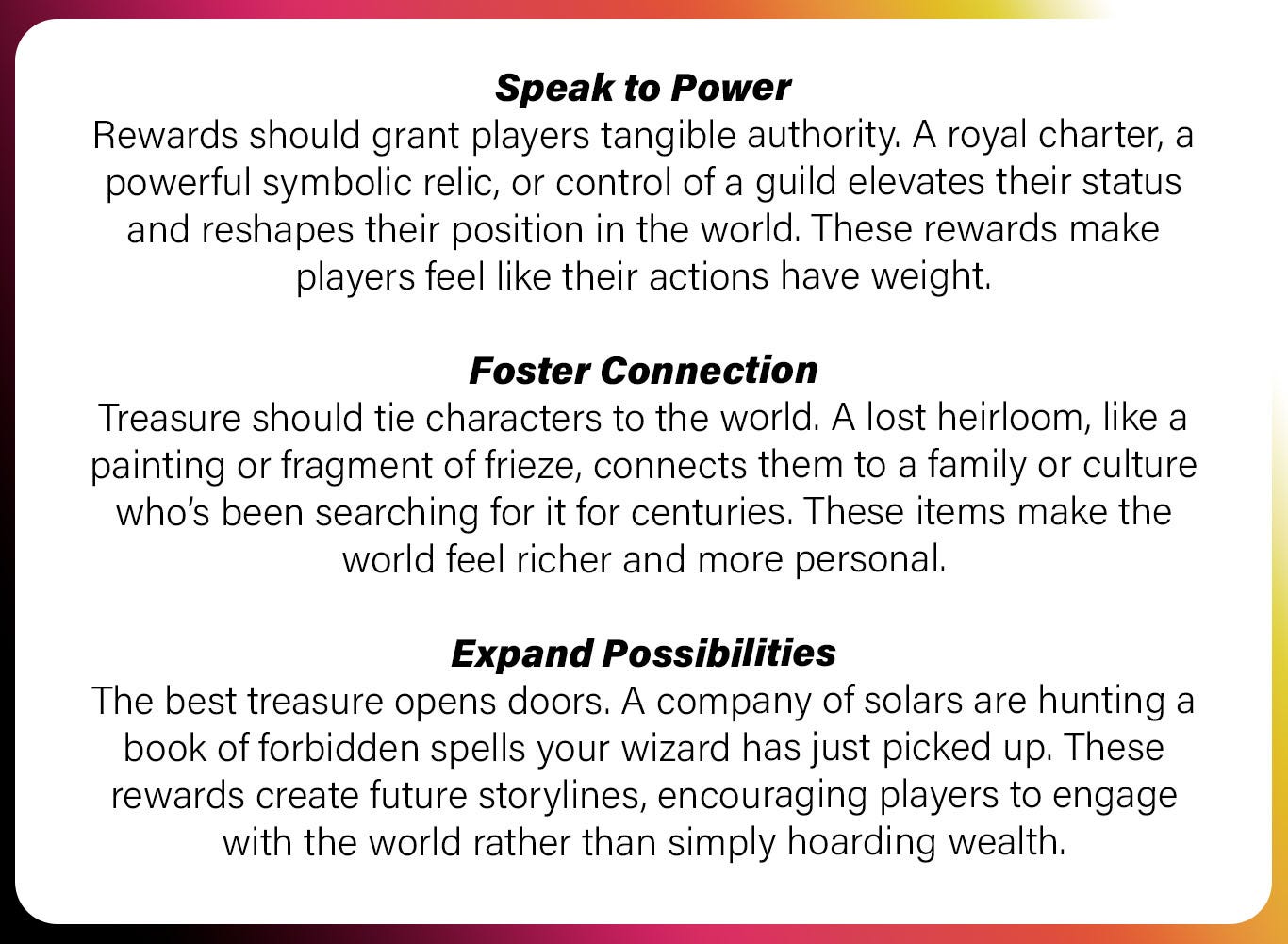

In storytelling, treasure is not a transaction but a transformation. The best rewards convey status, influence, and power. They elevate characters in the world, reinforce their connections to it, and open new opportunities. They are, quite literally, treasured — something to be shown as a symbol and held dear.

Take the Portrait of a Young Man. Like it, many other paintings from the era in which it was made are examples of the Mannerist style and later Nazarene movements.

It, alone, is not incomprehensibly unique.

But what makes it unique compared to its contemporaries is the story behind the story: where the location of the painting is, how it ended up there, who has it, or, worst case, when it was destroyed and why.

The legacy of the painting supersedes the objective worth of its materials and artistic intent. When creating rewards for players, think along the same lines: focus on what the treasure means and does.

Here are three ways to approach it:

You can see from the above options that these items aren’t magical (or at least not presented as such). Their value in coins isn’t listed or even implied.

But their connections to people, factions, histories, and crimes create a legacy to which the players can affix themselves. The items become less about a simple transaction for small, ephemeral power increases and more about creating a lasting impact on the world and those within it.

When thinking of rewards in your games, leave gold in the coffers. More powerful treasures, such as historical items, strongholds, and titles, can speak volumes, whereas coins and gems tell mere sentences.

Besides, it’s not as though these things can’t be later traded for coins if needed! 😉

This article is brought to you by the following paid subscribers who make this newsletter possible:

Azzlegog

Colin

Michael Phillips

Mori

Space Pirate

A cool case for using actual history and historical items to generate ideas for your own campaign.

This was a fun read! I love when interesting real-life stories inspire TTRPG goodness!